Tom Watson, the great golfer, once said that the difference between a professional and an amateur was that an amateur attempted a shot that he could pull off three out of ten times, while a pro only tried one he could make nine out of ten times. I think some of this logic applies to furniture making as well.

The quadralinear leg -- one that displays four sides of quartersawn figure, is a hallmark of refined arts and crafts furniture. A quick browse through the Stickley catalog will not only show you many examples, but even feature a blurb about their pride in this technique. In order to create this effect you must work through some complicated joinery -- joinery that has the potential to cost you a two-stroke penalty (forcing the golf metaphor) in the blink of an eye.

Sure, you could mill a big chunk of 12/4 oak for your legs, but you would have quartersawn figure on only two legs. You could also add quartersawn veneer to the plain figure sides, (a technique in a recent

Fine Woodworking video) but history and Robert Lang says that it will split, and your furniture will be flawed. The answer seems to lie in mitering four long pieces of quartersawn oak to create a quadralinear leg.

I decided to test three methods, all of which can be found on various sites, to see which one results in the highest percentage of success without making you lose your sanity. Just to lay the groundwork, all pieces are 2 1/2" wide and 13/16" thick.

The Drawer Lock Miter Bit Method

This has been my method in the past. If you are willing to pony up 75 bucks for a bit and you have a fairly robust router, a router table with infinite adjustment capabilities, and the patience of a saint, this might be your first choice. By running one edge of your leg piece on its side, and then the other side flat on the table, you will have a joint that has a 45 degree miter on the outside and some internals that lock it together with its mating piece.

All this works in theory, but in practice I've found it to be highly unsatisfactory. There are just too many variables -- the height of the bit, the distance of the fence, the speed of the router (I've tried everything from 13,000 to 18,000 rpm), and grain direction. I've used featherboards, I've trimmed of edges on the tablesaw, I've handplaned the flats, and everytime I do it I feel that the results are in the laps of the woodworking gods and require some large amount of jiggery-pokery to get a result. Sometimes it is dead perfect; sometimes it is not. Also, no matter how you try to collect the dust, your shop looks like the Sahara Desert in a heartbeat.

If you approach your furniture building like an accountant, this might be for you, but I doubt it. There must be a better way.

The Tablesaw Miter Joint

Robert Lang does an excellent job of explaining this method in his second collection of

More Shop Drawings for Craftsman Furniture. This joint looks most like what I believe the early factory furniture makers used and it has a lot going for it. It feels authentic and once you work out your chosen dimensions, you can put together a detailed plan that allows you to cut from start to finish with no guesswork.

But . . . quartersawn white oak is by nature fairly reactive wood, and as you cut it, it will bend and twist a bit rendering the internal joint faces inaccurate. You then must add a little play in order to make the money faces (the miters themselves) fit without gaps. Also, the required cuts force me into positions I try to avoid when using a table saw. There are times when you are referencing knife edge cuts awkwardly and even though I use push sticks and featherboards, I started to get the heebie-jeebies.

The results are better than with the router table, but it wasn't a silver bullet. I got to thinking, the only thing that really matters are the miters themselves -- the internal joint stuff is only there to hold it in place while you clamp it up. If you can find a way to clamp it accurately, then all you need are four mitered pieces, right?

Four Mitered Pieces

To quote Walter Sobchak from

The Big Lebowski, "The beauty of this plan is in its simplicity." If you start with 2 1/2" wide stock, set your fence to 46 mm (if you have a Beisemeyer fence it is the most accurate mark), and adjust the blade to 45 degrees, you can cut miters on both sides of the piece. You are now done with the machining.

Now, here's the trick. Set the pieces side-by-side, edges touching and apply long strips of packing tape.

Now flip the bundle over and apply glue to the faces.

Now roll up and apply a couple of quick clamps where necessary.

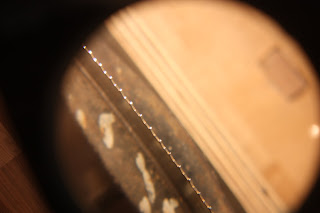

There is plenty of glue surface and you are free to insert a square block in the middle if you want to add stability. I don't think that it is necessary since any stress on the piece would be the tenon pushing on end grain. The method is quicker, kicks up less dust, and is safer than most others. The tape provides much more pressure than you would expect and the glue line is as small as on a perfectly executed Drawer-Lock Miter. The difference is that it is perfect nine out of ten times, not three out of ten. I like it a lot, and I'm going to retire my old technique. But enough about method.

I've glued up the panels to the chair and placed the grooves in the sides of the completed legs to hold the corbels and the panels.

The dry fit looks something like this.

Next, assembly and finish.